Research point-

The evolution of landscape painting

Landscape painting has already evolved from the art of the Renaissance and Dutch Golden age painters by the time we approach the eighteenth century.

Before the 18th century, landscape had been inferior to the main subject, which was often a religious or classical scene. By the time of the Dutch masters in the late 16th and 17th centuries landscapes had attained more significance as subjects in their own right. At this time, painters weren’t so constrained to earn their living by painting only religious paintings. Good examples of these early landscape paintings are ‘The Castle at Bentheim’ by Jacob van Ruisel (1628 – 1682) and ‘A River Valley with a Group of Houses’ by Herculaes Segers (1589 – 1633). You can see how they focused on a main subject in their painting, such as architecture, to build their composition around, rather than the view as a whole, as we see in later, more modern paintings.

The Castle at Bentheim by Jacob van Reusel

The Castle at Bentheim by Jacob van Reusel

A River Valley with a Group of Houses by Hercules Seghers

A River Valley with a Group of Houses by Hercules Seghers

Eighteenth century

In the eighteenth century it was still commercial for an artist to paint portrait commissions and yet some showed a distinct preference for painting the landscape behind the sitters. This can be seen in Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (1748 -50). Order and structure was the main theme, in eighteenth century English landscape. This is shown in works by the first major British landscape artists Richard Wilson with “The Destruction of Niobe’s Children” (1760), Thomas Gainsborough with “Mr and Mrs Andrews” (1749), William Marlowe with “The Pont du Gard Nimes” (1767), John Robert Cozens with “London From Greenwich Hill” (1791), and Thomas Girtin with “The White House Chelsea” (1799). In the 18th century, watercolour painting, mostly of landscapes, became an English speciality. Towards the end of the 18th century, Thomas Gainsborough, Thos Girlin and John Cotman had all contributed notable landscape paintings, the last two using watercolours which by then had become an established medium, but they had begun to use it in a different way. Until then it had been used largely as a means of tinting an underlying drawing but Cotman and Girlin laid down broad washes to build up and define planes and shapes tonally in a technique more similar to glazing with oils or tempera but without the opacity. By the beginning of the 19th century the English artists with the highest modern reputations were mostly dedicated landscape artists, showing the wide range of Romantic interpretations of the English landscape found in the works of John Constable, J.M.W. Turner and Samuel Palmer.

Mr and Mrs Andrews by Thomas Gainsborough

Mr and Mrs Andrews by Thomas Gainsborough

The Destruction of Niobe’s Children by Richard Wilson

The Destruction of Niobe’s Children by Richard Wilson

William Marlowe The Pont du Gard Nimes

William Marlowe The Pont du Gard Nimes

London From Greenwich Hill by John Robert Cozens

London From Greenwich Hill by John Robert Cozens

The White House Chelsea by Thomas Girtin

The White House Chelsea by Thomas Girtin

Nineteenth century.

Landscape art intensified in the 19th and 20th century with the Romantic Movement and it has set many milestones for the history of landscape art. The Romantic movement intensified the existing interest in landscape art, and remote and wild landscapes, then became more prominent. As the Industrial Revolution altered the traditions of rural life, the old hierarchy of subjects crumbled. The viewing of Constable and Turner’s works in London had a major impact on Claude Monet and his fellow Impressionists.

The German Caspar David Friedrich had a distinctive style, showing the powerlessness and vulnerability of mankind set against nature, as seen in his painting “The Monk By The Sea” (1908-10). In this painting the artist has used scale to convey his theme. The isolated figure of the monk is tiny in comparison to the vast sky and sea, giving a great atmosphere. Friedrich’s work had a lasting impression on James Abbot McNeil Whistler, as seen in his “Nocturne” paintings. The use of a strong composition and varying tones can be seen in ‘Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Battersea Reach”. The hard dark lines of the industrial dockland contrast with the pale green-grey of the misty sky and the reflected light in the water below.

“The Monk By The Sea” by Casper David Friedrich

“The Monk By The Sea” by Casper David Friedrich

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Battersea Reach by James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Battersea Reach by James Abbott McNeill Whistler

In the 19th century, the biggest development that happened in the field of art was the invention of photography which would greatly influence the landscape painters’ compositional choices and which has given more freedom to artists to draw the landscape as for their interpretations, paving the way for Impressionism. The Impressionists, comprised of artists including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, would devote most of their careers to studying and painting the landscape, working most often out-of-doors. The influence of Courbet’s distinct use of paint and the way he structured his landscape views extended well beyond Impressionism, deeply impacting the work of Cézanne and Van Gogh, as well as painters in the 20th century.

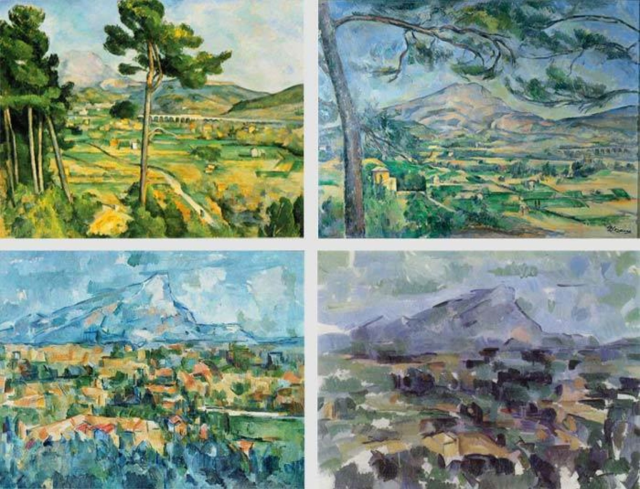

Paul Cézanne was a prolific French artist who’s work is broadly post-impressionist and formed the bridge between late 19th century Impressionism and the early 20th century Cubism. The many views of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire painted between 1882 and 1906 rank among the greatest landscapes ever painted. He soon became interested in the representation of Mount Sainte-Victoire, a 1011 meter (3,317 ft) high near Aix-en-Provence. Cézanne used different points of view in his “Montagne Sainte-Victoire” paintings to show different representations of its environment. The drawing and brushwork are more impulsive throughout, but evolves through the years.

Vincent Van Gogh is most famous for his bright expressive colour in his later landscapes, such as “A Wheatfield with Cypresses”, painted from the asylum in Saint-Rémy in 1889. He regarded this landscape as one of his “best” summer canvases and repeated the composition three times: first in a reed-pen drawing and then in two oil variants. The tall dark cypress tress at one side offer a powerful contrast to the bright blue rolling clouds. Van Gogh’s impasto texture adds to the sensation of movement in the piece.

Paul Cézanne Montagne Sainte-Victoire

Paul Cézanne Montagne Sainte-Victoire

Vincent Van Gogh A Wheatfield with Cypresses

Vincent Van Gogh A Wheatfield with Cypresses

Twentieth century to now.

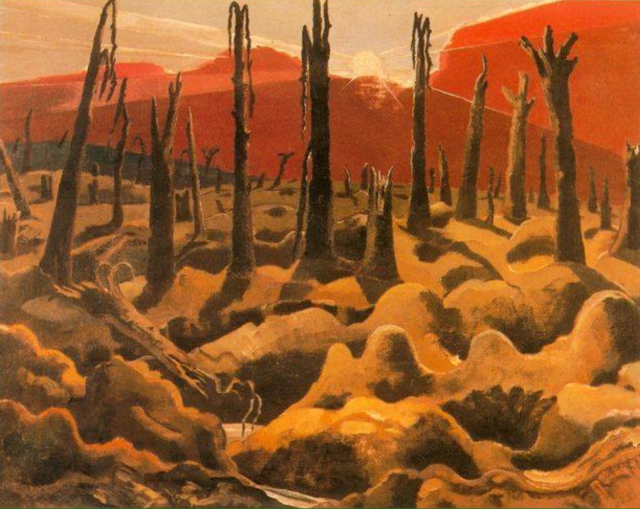

The First World War was the first conflict to create a variety of artistic output from those who fought on its battlefields. This gave vary different portrayals of landscape, to reflect the atrocities and darkness of war, and artists like David Hockney, John Singer Sargent, Eric Kennington, William Orpen, and John and Paul Nash captured this. Paul Nash’s landscape painting, with the bitter title “We are Making a New World”, represents a scene of devastation that could be anywhere on the Western Front. There are no people or any of the details in the painting to distract from the broken tree stumps, shellholes and mounds of earth, and the sun is a cold white orb. The dismembered trees and traumatised fields became a metaphor for the wider destruction and suffering of the war, and the nature in this way became a means of understanding the war and modernising landscape painting.

In contrast, contemporary landscape artists have experimented and evolved from these predecessors and took inspiration from them, as well as taking their own modern take. One artist I liked was Scott Naismith, who spends much of his time travelling around the country looking for inspiration for different depictions of the Scottish landscape. He uses vivid colours in a vigorous strokes to represent the fast changing conditions of the West coast of Scotland. Colours often becomes a emotional response and he tries to portray this energy which he handles the palette knife and brush. I love his use of colour and the impressionistic brushstrokes that he uses to portray landscapes. The use of bright colours give an energy and movement to the piece and gives the landscape a personality of its own.